Concept of Expectation

Expectation, from the Latin exspectātum (“awaited” or “in sight”), is the hope of achieving or accomplishing something.

• Ways of categorizing people through clues and information, predicting their behavior and attitudes;

• They are mutual, meaning the person with whom we interact also develops expectations about us;

• It is usually associated with a reasonable possibility that something will happen. To this end, there is generally something that supports it; otherwise, it becomes nothing more than an irrational hope or one based solely on faith.

Example: If there are many clouds in the sky, the expectation is that it will rain soon. Therefore, the response to this expectation is not to leave the house without an umbrella to avoid getting wet when the first drops fall and to not be caught off guard.

• Expectations arise in uncertain situations, when it is not yet confirmed what will happen. Expectation is what is considered most likely to occur; thus, it is a more or less realistic assumption;

The Brain as a Prediction Machine

According to an increasing number of neuroscientists, the brain is a prediction machine that constructs an elaborate simulation of the world, based both on expectations and past experiences, as well as the natural data that reaches our senses.

The Eyes

Studies have shown that people see things according to their own expectations; in other words, the eyes influence our expectations depending on the light and the context in which we observe situations. Even the time of year can influence how the brain processes ambiguous information.

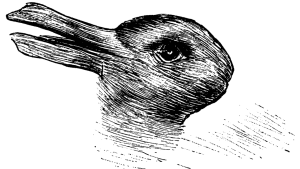

Swiss scientists conducted an experiment at the entrance of a zoo, asking visitors what they saw in a specific image. This famous ambiguous image is an optical illusion, which was presented to participants as follows:

The results of this study show that during the month of October, 90% of zoo visitors described seeing a duck, a bird looking to the left. However, when the same question was asked during Easter, this response dropped to 20%, and most people instead observed a rabbit looking to the right.

Expectation is also well-known in the world of gastronomy. An experiment involving astronaut food was conducted by changing the label from “space food” to the description of the actual contents of the packaging. This altered the astronauts’ perception of taste.

Placebo Effect

When taking medication, its effects result from the chemicals it contains. Thus, one expects a specific result when taking it. However, studies have shown that this outcome is often possible even without taking the medication. This means that our body has the ability to produce certain chemicals purely through suggestion or expectation. This phenomenon is called the placebo effect.

Since the birth of modern medicine in the 18th century, doctors have been aware of treatments that relieve patients solely through their belief in the treatments themselves. For a long time, the placebo effect was regarded more as a diagnostic tool than a treatment.

Today, we know that positive expectations can offer more than emotional comfort, providing genuine relief for various conditions, including asthma, Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, and chronic pain. The mind-body connection is real and potentially powerful.

In fact, there are already studies showing that even when patients are aware they are taking a placebo, they respond in the same way as they would if they were taking an active medication. Let’s look at the example of a study by psychologist Cláudia Carvalho, published in 2016, where participants were given a bottle of capsules clearly labeled ‘Placebo Capsules, Take 2 times a day’. In this clinical trial, the psychologist showed a video to reinforce the idea, after explaining that the pills contained no active ingredient; she also added that it was not expected for people to feel an optimistic mood for the placebo to have an effect, as simply taking the pills would be the treatment.

After being fully informed that the capsules contained no active ingredients, participants reported a 30% reduction in both their usual and maximum pain levels within three weeks.

A follow-up study in 2020 revealed that the benefits persisted for five years, suggesting the participants retained a placebo response mechanism that helped them manage their condition.

Nocebo – The Negative Effect of Expectations

There is a phenomenon, opposite to the placebo effect, that scientists and doctors have called nocebo. Just as we can be influenced by positive expectations, sometimes we are also influenced by negative expectations. Take the case of a man in Tennessee who was diagnosed with esophageal cancer in the 1970s. He underwent surgery where the tumor was successfully removed, but subsequent exams showed that the cancer had spread to the liver. They told him that he would be lucky if he survived until Christmas, and he barely made it through the holidays with his family before passing away at the beginning of the year. It turns out that when the autopsy was performed, they discovered that the tumor in his liver could not have killed him; there had been a mistake in the diagnosis.

The potential of negative thoughts and negative expectations has been well known since the early days of modern medicine, even before the concept of nocebo.

Can We Die from Expectation?

Extreme nocebo responses have been documented in recent years, although they remain rare, they do exist. Take the case recorded in Minnesota in 2007 of a man who was extremely depressed and volunteered to participate in a clinical trial for an antidepressant drug. He enrolled in the hope of feeling better, but the effects didn’t last long, and in a moment of desperation, he decided to take all 29 capsules from the box. He quickly regretted it and asked a neighbor to take him to the hospital, where he was helped in a state of collapse.

He was trembling, drowsy, pale, and had concerning blood pressure. After some tests, the doctors at the hospital concluded that there was no toxicity in his body.

With no improvement in his condition, the hospital contacted the clinical trial team, who confirmed that the man had not taken the active ingredient; however, based on his vital signs, he was in overdose. Fortunately, after speaking with him, he made a full recovery.

It can thus be said that ‘death by expectation’ is possible; fears and anxieties about illness can contribute to heart disease in a surprising number of people. It is important to remember, however, that extreme nocebo effects can have powerful consequences on our daily health and well-being.

Group Contagion of Expectation

Our brain has a system called the mirror system. This system consists of a network of neurons known as mirror neurons; these neurons, initially described in primates, are linked to vision and movement and allow learning through imitation. According to studies, thanks to these neurons, we can feel happy simply by being around happy people if we have regular interactions with them.

In fact, the same studies show that happiness increases by 10% through the friend of a friend and even by 6% through the friend of a friend of a friend. These findings are truly important for our mental health, revealing how much it depends on our social circles.

How Expectation Affects Eating

I’ve always joked about this topic, always saying that I ate French fries imagining that they were good for my health, and it turns out I wasn’t completely wrong! I won’t be fundamentalist, but what I’m about to write will give you something to think about. Our expectations about the nutrients in the food we eat directly influence our body’s responses to food, including digestion (assimilation and absorption of nutrients) and metabolism (the use of those nutrients as energy for our cells).

When we think we are eating fewer calories than we actually are, our body responds as if it were true: it feels less satisfied, experiences more hunger, and burns fewer calories to preserve fat deposits.

Harnessing Negative Emotions for Positive Outcomes

Over the last few centuries, various theories have been tested on how the emotions felt during moments of anxiety can be used to our benefit. Psychologist Jeremy Jamieson from the University of Rochester in New York was at the forefront of scientific research in the early 2000s. His interest focused on how student-athletes managed their anxiety. He noticed that some athletes would often feel excited and thrilled before a game, but would become truly nervous before an exam. Both were high-pressure situations, so he questioned how stress could be helpful in one context and a hindrance in the other.

Jamieson suspected that it had to do with how both events were perceived and evaluated by the students. In the case of the game, the athlete interpreted their nervousness as a sign of energy, while in the exam, the same nervousness was seen as a sign of imminent failure. These expectations could then become self-fulfilling prophecies, shaping the brain and body’s responses to stress.

Why does the evaluation of what we feel have such power? For researchers like Jamieson, it all has to do with the predictive ability of our brain, balancing our mental and physical resources with the demands of the task to plan an appropriate response.

If we see our anxiety as debilitating and reducing our performance, we are reinforcing our expectation that we are at a disadvantage and will fail—and the brain will respond to the threat, preparing the body for danger and potential harm. But if we feel our heart racing as a sign of energy for a potentially important and rewarding event, we are reaffirming the idea that we have everything we need to be successful. ‘The stress response, instead of being something to be avoided, actually becomes a resource,’ says Jamieson.

The brain can thus focus on the task at hand without being constantly on alert for any threats, and the body can prepare to perform the action to its maximum capacity and potential, without the risk of harm.

It’s important to emphasize that the intention is to change the interpretation of our anxiety and not suppress the feelings themselves. With this reappraisal technique, you don’t have to worry about being short of breath or your heart beating too fast. What you need to remember is that these responses are not a sign of weakness, but rather that they can and should help you perform your task to your best potential and thus develop your future.

Application of Resources

Following this reasoning, studies have shown that our expectations also influence the use of our resources and the completion of tasks themselves. This means that if we believe a particular task will tire us more than another, it is likely that this task will indeed use up more resources, and we end up more tired.

Expectations also work for our willpower. If we have a low expectation of our willpower, it makes sense that our brain will work in response to that expectation, meaning it will reduce glucose consumption, conserve energy reserves, and avoid exhaustion.

The opposite can also happen. If a person believes they have unlimited resources, the brain will release all the necessary energy, since it is not afraid that it will run out. It will use all available resources because it believes they are limitless.

Pygmalion Effect – What we think of others and what others think of us

In the 1960s, psychologists Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson conducted an experiment in a primary school, which consisted of administering an intelligence test to the students at the beginning of the year. The results were given only to the teachers, and the students with the highest scores were highlighted. At the end of the year, it was found that the students with the highest IQ had performed the best. The twist is that the information given to the teachers was actually random. In other words, the students’ names with the highest IQs were not those who actually had the highest scores but were instead randomly chosen from the list of all the students.

This study demonstrated that the expectations teachers had about the students influenced the students’ performance throughout the year.

It is observed that the expectations we have of others can influence their performance, just as the expectations others have of us can also influence us. This phenomenon was called the Pygmalion effect by Rosenthal and Lenore.

I expect that after reading this article, you will have a clearer idea of how expectations can shape your life and the lives of those around you, and that this somehow helps you become more aware of your journey and your experience in itself. Despite all that I’ve written, which is quite limited, much more can be said about this subject. It is known that no matter how much we make the practice of these skills or competencies a habit, it is not always just up to us to control our expectations and beliefs. Let’s take the example of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, in which so many people with the best skills to handle stressful situations found themselves depressed and lonely during the continuous lockdowns.

Let’s be compassionate and generous with ourselves and remember that we are always progressing. Thanks to advancements in neuroscience, we now understand the concept of neuroplasticity, which is the ability of our brain to renew neural connections and change, even creating new connections in response to circumstances. These connections will determine our own abilities. Let’s be kind to our personal transformation, for it doesn’t happen overnight and is not always linear. By being aware of our difficulties and limitations, we also recognize that others around us may face challenges, and this gives us a very supportive and humble perspective on the path ahead.

Thank you for reading to the end. If you have any comments or questions send me an email ana.cecilia.autora@gmail.com

This article was inspired by the book “The Expectation Effect – How your mindset can transform your life” by David Robson